Revealing Sections of the Alexandria Canal

Revealing Sections of the Alexandria Canal

Alexandria Canal, Site 44AX0028

901 N. Pitt Street

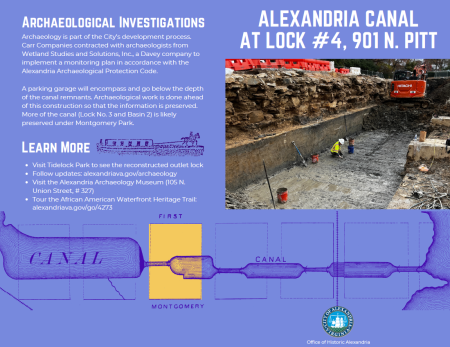

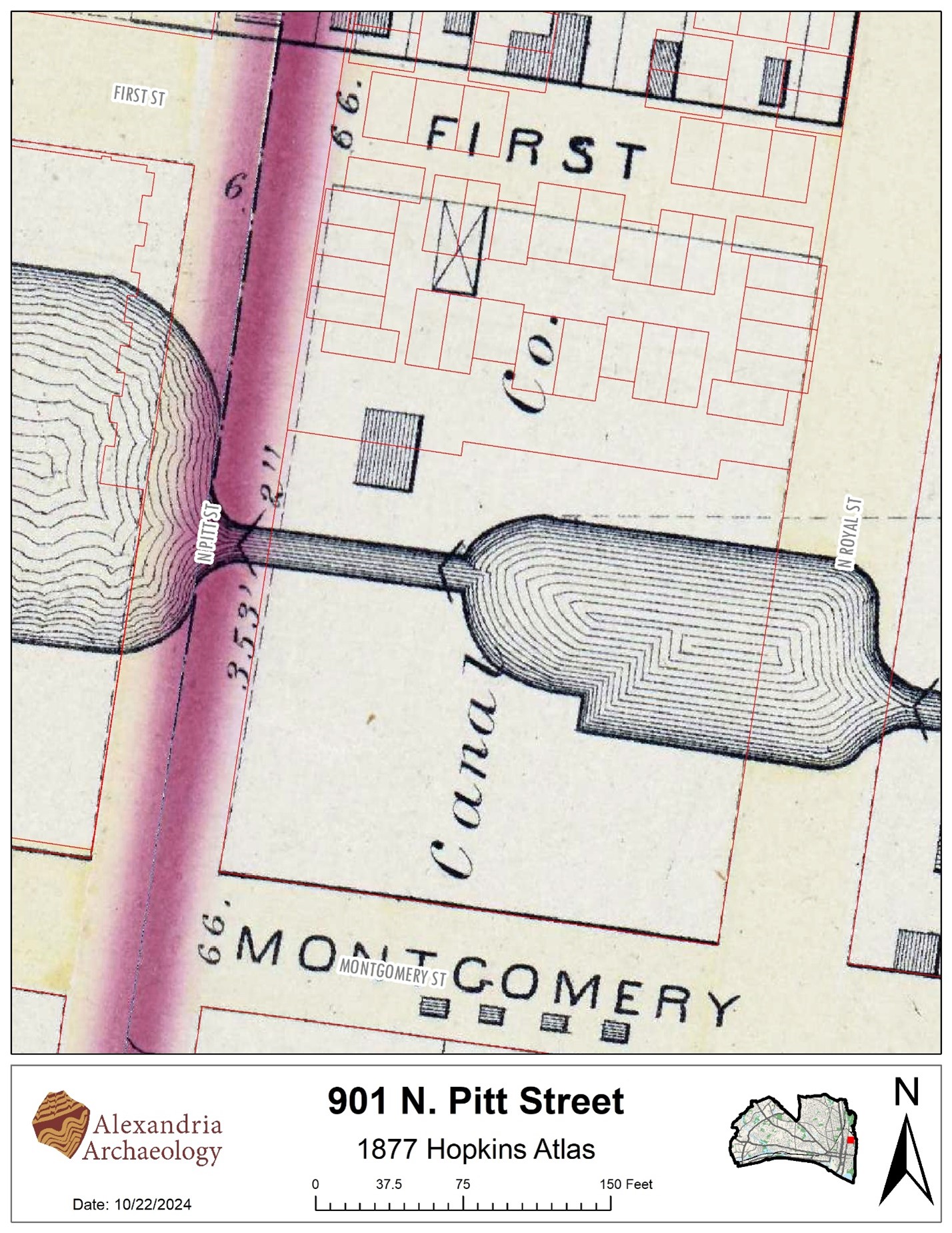

Historic maps show that the ca. 1840 Alexandria Canal, specifically the fourth lock and third basin, lies beneath this portion of the city block bounded by Montgomery St., N. Pitt St., N. Royal St., and First St. Alexandria Archaeology anticipated that the masonry remains of this large-scale piece of historic infrastructure may be preserved despite 20th century development on the block. As part of the redevelopment of the Waterman Place office building, Carr Properties contracted with professional archaeologists from Wetland Studies and Solutions, Inc., a Davey company, to implement an archaeological monitoring plan in accordance with the Alexandria Archaeological Protection Code.

Archaeologist unveils rare 1800s Alexandria Lock and Basin find

Interview with City Archaeologist Eleanor Breen, on Good Morning Washington, ABC7 News, Wednesday, January 15, 2025

February 2025 Update: Canal Stone Removal

City staff collaborated with Carr Properties to salvage and relocate a sample of historic Alexandria Canal stones, uncovered during construction at 425 Montgomery Street, for eventual re-use within a waterfront park. The canal stones have been temporarily relocated to the adjacent Montgomery Park for future integration into the construction effort associated with the Waterfront Flood Mitigation Project along the Potomac River. Road closures for the initial relocation to Montgomery Park took place in February and are now complete.

January 2025 Update: Viewing

On January 19th, the City of Alexandria and Carr Properties hosted a viewing event at the canal site. More than 550 people braved the elements and came out to see the uncovered Alexandria Canal lock number 4 and pool number 3. Archaeologists from Alexandria Archaeology and Wetlands Studies and Solutions, Inc. were on hand to talk about the history of the canal and efforts to document the archaeological remains prior to their removal.

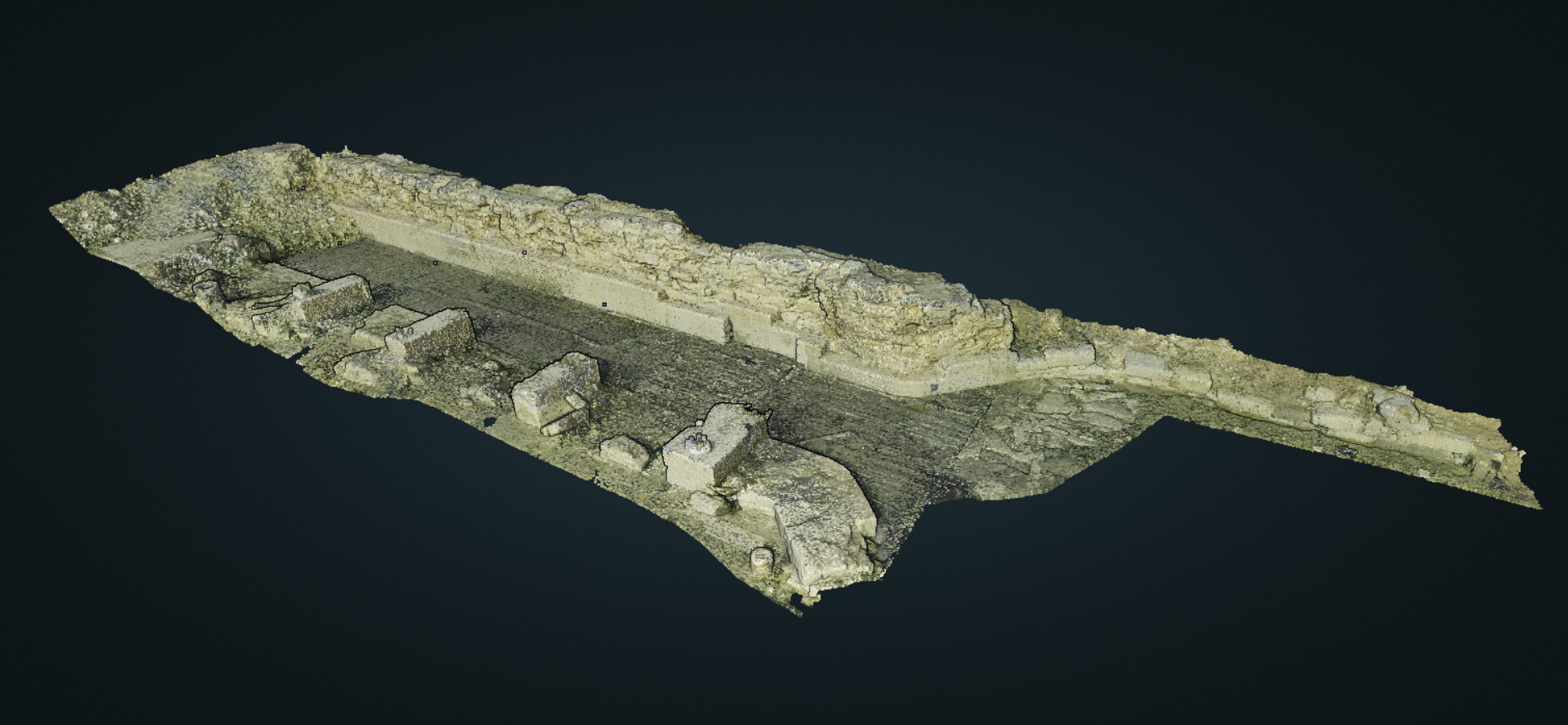

A parking garage will encompass and go below the depth of the canal remnants. Archaeological excavation and digital documentation were done ahead of this construction so that the information is preserved. As a part of this documentation process, Wetlands 3D-scanned the canal lock and pool using a laser scanner. Using this machine, archaeologists recorded the locations of millions of points along the surface of the canal, resulting in an extremely detailed 3D model of the canal lock and basin that will help future researchers study the canal after it has been disassembled.

Beginning February 20, workers began carefully disassembling the stone walls of the canal lock and basin. The stones will be moved across the street to the adjacent Montgomery Park, where they will be stored for eventual reuse along the City’s waterfront as a part of the Waterfront Flood Mitigation Project.

December 2024 Update: Field Excavations

In December 2024, working under an approved Resource Management Plan, archaeologists began to uncover more of the canal feature. Using a backhoe, they removed the foundation of the 1980s office building which formerly stood here as well as earlier 20th century fill soils. Beneath these are the partially preserved remains of canal lock number 4 and the third basin which sat to the east of it.

The Alexandria Canal had a total of four lift locks located between the turning basin immediately west of this site, and the canal’s outlet at the Potomac River, four blocks to the east. These locks allowed canal boats to ascend or descend the approximately 40 feet in elevation between the river and the rest of the canal that went to Georgetown where it connected to the C&O Canal. Between these four locks were three basins, which allowed for staging of boats traversing this section of the canal and for the storage of water which was required to operate the locks.

While not all of this canal lock has survived archaeologically, the sections that remain provide us with an excellent look at the way it was constructed and here are some preliminary observations.

The masonry walls are sitting on top of a wooden base consisting of layers of planking on top of what appears to be a wooden timber frame. Visible on the floor of the canal lock at the east end are the remnants of what we interpret to be a triangular structure called a mitre sill. This acted as a kind of door stop that the lock gates rested against when in the closed position and would have supported the lock gates when the lock was filled with water.

Archaeologists will continue to expose and clean portions of the basin before they digitally document the canal lock and basin. After the information about the lock and basin remnants is preserved through photographs and documentation, they will then be removed as the construction project continues. City departments are exploring the possibility of saving some of the stones for future reuse in park or other projects.

Fall 2024 Update: Discovery

In the fall of 2024, a preliminary round of mechanical trenching exposed the north stone wall of the lock and basin. The south side of the lock wall appears to have been disturbed by the construction of the previous office building.

History and Previous Archaeology

“The Alexandria Canal, begun more than 150 years ago as a seven mile segment in a regional commercial navigation system of 185 miles, helped to create and to shape regional growth patterns in and around Alexandria” (Hahn and Kemp 1992:xi).

The Potomac Company formed in 1785 with the goal of building a canal that would extend shipping traffic to western Maryland by circumventing the falls of the Potomac River. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company took over the canal business in 1828, after the Potomac Company went out of business. The C&O Canal Company’s objective was to create a continuous canal that eventually stretched from Georgetown to Cumberland, Maryland.

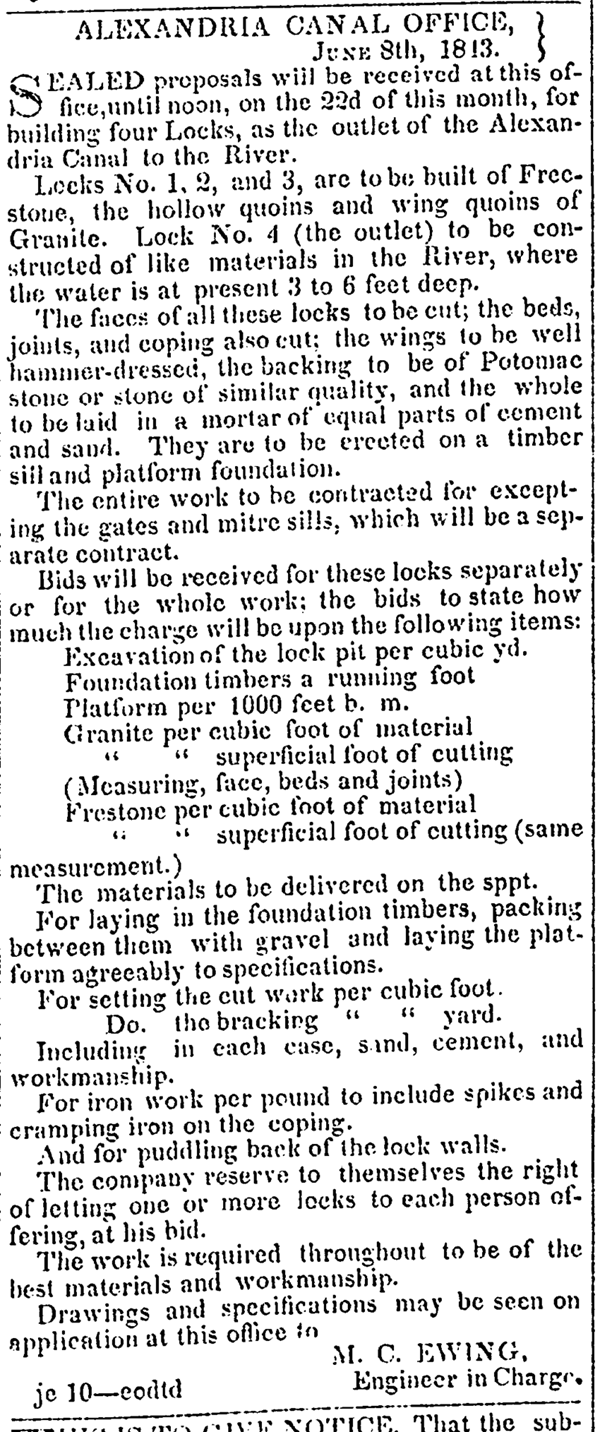

Alexandria’s merchants and shipowners sought to build an extension from the terminus of the canal at Georgetown to the port of Alexandria and profit from this access to western trade. This required the building of a1,000-foot-long aqueduct bridge over the Potomac River. On December 2, 1843, the Alexandria Canal was officially opened to trade and navigation and the first canal boat arrived at Alexandria. In 1845, the canal company completed construction of four lift locks and three basins or “pools” between the Potomac River and N. Pitt Street.

Surviving records that document the construction of the canal are incomplete but provide a glimpse of how the canal was built and by whom. Major William Turnbull of the Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers published a meticulous report of his work overseeing the building of the Potomac Aqueduct bridge at Georgetown. In it, he documented the tasks performed by mechanics, carpenters, masons, and laborers (and especially the challenges of convincing these laborers to work difficult and dangerous jobs in bad weather). Civil Engineer Maskell C. Ewing maintained a set of engineering notebooks as he worked on completing the canal in Alexandria. In these notebooks, he recorded various surveying notes (elevations, distances, and measurements), deliveries of construction supplies, payments to various parties, the weather, and the arrivals of canal barges from Georgetown and the tolls they paid. He also recorded the daily activities of his contractors and their “forces” as they worked to finish the canal’s locks.

The identities of Turnbull’s laborers and Ewing’s forces are not mentioned in these documents, but we know that at least some of them were enslaved. British abolitionist Edward Strutt Abdy visited the United States in 1833 and 1834 and published an account of his trip in Journal of a Residence and Tour in the United States of America. In it, Abdy described a trip through Alexandria and a fireside conversation he had with one of the contractors on the canal, writing, “He [the contractor] had been in the habit, for some time, of hiring a gang of sixty or seventy slaves, paying for each at the rate of seventy-five dollars a year.” The contractor paid the enslaver of each of these men annually, and in exchange, they were forced to work for him on the canal. Frequently, enslaved people who were ‘hired-out’ in this manner would receive a small payment for their work, but Abdy does not record if that was the case here.

In the years of operation before the Civil War, the Alexandria canal primarily shipped manufactured products and fish and received agricultural products. The majority of the descending, or incoming, cargo shifted after the opening of the C&O Canal to Cumberland, Maryland in 1850 from agricultural products to coal. The Alexandria Canal went dormant during the Civil War, disrupted by the movement of Union troops and supplies and the conversion of the aqueduct to a wagon road to facilitate that movement. The canal did reopen after the Civil War, but it was continually plagued by the need for expensive repairs. Ultimately, railroad transportation eclipsed the canal system and it was abandoned in 1886.

Remnants of the canal were visible on the landscape at least through 1937. In Virginia Knapper’s oral history, she shared her memories of the Black neighborhood known as Cross Canal and described what the canal looked like in the early 20th century. Knapper remembered a bridge across the canal and skating in her shoes where the water still formed and froze during the winter.

Nearly 50 years ago, Alexandria archaeologists uncovered the outlet (or tide) lock and pool No. 1 at the mouth of the Potomac River. Over the course of about six years, archaeologists, the Alexandria Archaeological Commission, developers, and engineers worked together to excavate, repair, rehabilitate, and interpret the outlet lock, basin, and associated wing walls of the easternmost lock. The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. An interpretive reconstruction of the tide lock stands today as the centerpiece of Tide Lock Park, a privately owned, publicly accessible park that helps residents visualize and understand the city’s historic landscape.

As developers began planning for new construction at the 901 N. St Asaph St. block in 2015, Alexandria Archaeology determined that the property had the potential to yield archaeological resources that could provide insight into industrial and transportation activities in 19th-century Alexandria. A preliminary assessment anticipated that there might be remnants of the Alexandria Canal turning basin situated on this property. Additionally, there was a “Spa,” or spring, adjacent to the turning basin, to the west, near a stream on this property that appears on the 1845 Ewing Map. The 1877 Hopkins fire insurance map indicates that there was a lime kiln structure present on the site adjacent to the turning basin. Archaeologists on contract with the developers monitored the construction work on the block and documented soil layers associated with filling in the basin and the brick culvert associated with the Spa Spring.

Further Reading

- Alexandria Canal at Lock #4, 901 N. Pitt. Brochure, Alexandria Archaeology Museum.

- History of the Alexandria Canal. Brochure, Alexandria Archaeology Museum and Department of Planning.

- Old Town North Historic Interpretation Guide. Completed by the City of Alexandria, Office of Historic Alexandria, with assistance from PRESERVE/scapes and Stantec, 2017.

- The Alexandria Canal: Its History and Preservation, Thomas Swiftwater Hahn and Emory L. Kemp. West Virginia University Press, 1992.

- The Alexandria Canal. Marking Time, Alexandria Times, September 6, 2007.

- The Industrial Archaeology of the Tide Lock and Pool No. 1 of the Alexandria Canal. Thomas S. Hahn, 1982. (On file at Alexandria Archaeology Museum.)

- Maritime Historical Report for Alexandria Canal Tide Lock Project. Thomas S. Hahn, 1982. (On file at Alexandria Archaeology Museum.)

- A Canal for Alexandria. Alexandria History, volume 1, pp. 17-28. Vivienne Mitchell, 1978.

- Alexandria Canal Tide Lock National Register Nomination.

- The Alexandria Canal: Tidewater Terminus of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal System. Alexandria Archaeology Publications Number 22. Keith Barr, 1989.

Historic Signage Related to the Canal

Alexandria Canal (901 N. Fairfax Street)

Potomac Yard (2501 Potomac Avenue)

- Crossroads of Transportation. Roads, passenger rail and the Canal also crossed through the Yard.

Alexandria Canal (525 Montgomery Street)